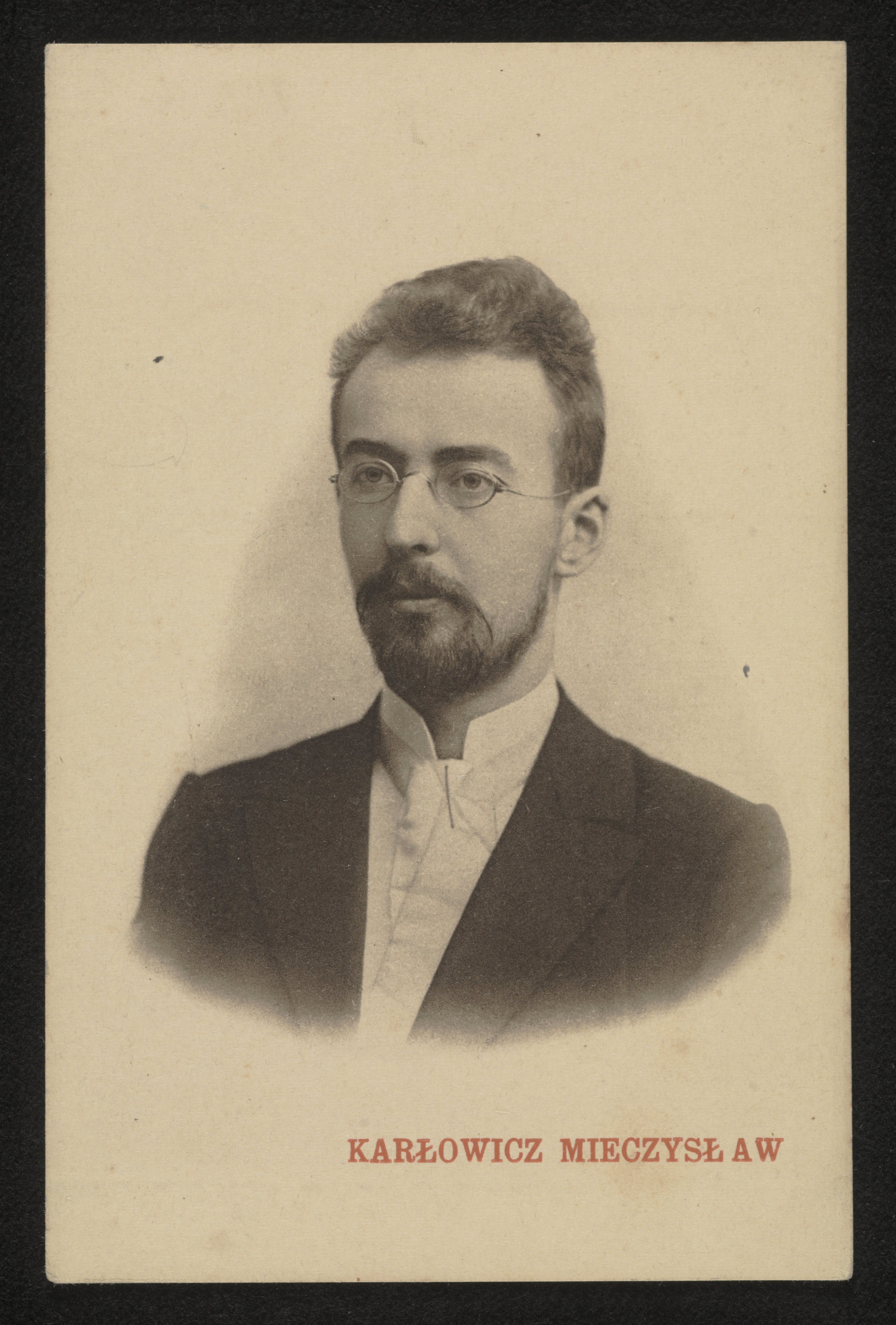

Born on 11th Dec. 1876 in Wiszniewo, died tragically on 8th Feb. 1909 in the Tatra. He spent his first six years of childhood in the family estate in Wiszniewo, Lithuania. Having sold the estate in 1882, the Karłowicz family moved to Heidelberg, then - in 1885 - to Prague, in 1886 - Dresden, and in 1887 they settled permanently in Warsaw. In Heidelberg and Dresden, Mieczysław Karłowicz attended prep schools, and from 1888 he went to the W. Górski public school in Warsaw. Brought up from his earliest childhood in a music-loving environment, during his stay abroad he became acquainted with operatic and symphonic music, incl. works by Bizet, Weber, Brahms, and Smetana. He strated taking private violin lessons in his 7th year of life, first in Dresden in Prague, then in Warsaw with Jan Jakowski. In 1889-95 he was a disciple of Stanisław Barcewicz, simultaneously learning harmony with Zygmunt Noskowski and Piotr Maszyński, later - counterpoint and musical forms with Gustaw Roguski. In the same period, he began composing. His earliest preserved piece, Chant de mai for piano, was written in 1893/94. In 1893-94, he attended lectures at the Natural Science Dept. of Warsaw University. In 1895 he left for Berlin, intending to study violin with József Joachim, but he failed to win a place on his course in Hochschule für Musik and therefore studied privately with Florian Zajic. Having decided to dedicate himself to composition, and began his studies with Heinrich Urban. Simultaneously, he attended lectures in music history, history of philosophy, psychology and physics at the Philosophical Dept. of Berlin University.

Most of Karłowicz’s 22 solo songs preserved to our day were written between the late months of 1895 and the end of 1896. In Berlin, he also acted as a music correspondent for EMTA. Apart from minor compositions, during his years of study with Urban he wrote music for Józefat Nowiński’s drama

The White Dove. In the late 1890s, he also began his work on the

“Revival” Symphony, which he completed independently after his return to Poland. In 1901, having completed his study, he returned to Warsaw. In 1903 he worked in the Managing Board of Warsaw Music Society, where he founded and directed a string orchestra.

Mieczysław Karłowicz dedicated himself wholly to one genre: the symphonic poem. In 1904-09, he wrote six symphonic poems op. 9 to 14. In 1906, he settled in Zakopane. His special love of the Tatra, which had originated many years before, was expressed in his activity in the Tatra Society, articles describing his mountain hikes, his passion for climbing, skiing and photography. He was also a pioneer of Tatra climbing. He died tragically in an avalanche in the Tatra, during a solitary mountain hike, on his way from Hala Gąsienicowa to Czarny Staw, at the foot of Mały Kościelec. He was buried at Warsaw’s Powązki Cemetery.

Even though Mieczysław Karłowicz wrote only one symphony, a work from his school years, he is now recognised as Poland’s most outstanding symphony writer because of his six symphonic poems. Apart from these six compositions, his oeuvre is rather small: the gracious Serenade op. 2 for string orchestra, the splendid virtuoso

Violin Concerto in A major op. 8 and the charming songs from his youth. What would his achievements have looked like, had he not perished under an avalanche at the age of 33? However great they might have been, in the area of symphonic music they remain - as they are - unsurpassed. Polish composers’ earlier work in this field - the compositions of Jakub Gołąbek, Antoni Milwid and Wojciech Dankowski in the 18th century, Józef Elsner and Karol Kurpiński in the 1st half of the 19th century, as well as Władysław Żeleński and Zygmunt Noskowski in the second half of that century - were at best a minor, secondary development in European music history. Thanks to his symphonic music, Karłowicz became one of the greatest masters of early 20th century symphonic music in the neo-Romantic style.

In his own time, however, Karłowicz’s neo-Romanticism came up against powerful, determined opposition. Young composers who wished, as Karłowicz put it, to “rub off Noskowski’s mark”, were, according to the eminent music historian Aleksander Poliński, “under the influence of some evil spirit that depraves their work, strives to destroy their individual and national identity and turn them into a kind of parrots who clumsily imitate the voices of Wagner and Strauss”. In Karłowicz’s work, critics saw a “modernist chaos”. They stressed the avant-garde character of his works, which was seen as the cause of their meagre popularity among the Polish audience.

For a composer looking for a new artistic direction, the prophet of the avant-garde was then Richard Strauss, in whose works Karłowicz found “a prophet’s insight into the future”. We know today that the future belonged to Debussy, Schönberg and Stravinsky, who entered the European music stage at the same time when Karłowicz expressed his admiration for Wagner and Strauss. Abroad, Karłowicz was consequently accused of eclecticism. After a composer concert in Vienna in 1904, presenting Karłowicz’s

Bianca of Molena,

Violin Concerto and the

“Revival” Symphony, a reviewer wrote: “It was a wasted effort travelling from Warsaw to Vienna only to show that we learnt our craft from Wagner and Tchaikovsky.” The influence of Tchaikovsky, Wagner and Strauss was criticised also after Karłowicz’s next concert in Vienna four years later, when the concert programme already included his mature works such as the poems

Returning Waves,

Centuries-Old Songs,

Stanisław and Anna Oświecim as well as

Sad Tale. This time, however, his “good orchestral technique” was recognised. It won recognition also in Poland, where both the critics and the audience finally became accustomed to the new style. After the concert on 27th April 1908 in Warsaw Philharmonic, at which the poem

Stanisław and Anna Oświecim was first performed, the press wrote: “The poem is modern in its wealth of ideas for instrumentation, the freshness and originality of harmony, which are not inferior to, but do not slavishly imitate Strauss.” And: “Karłowicz has his own special way of developing the modern orchestral colour derived from Richard Strauss, and he makes imposing achievements in this field.” The following concert in the Philharmonic - on 22nd January 1909 - was a complete success. Grzegorz Fitelberg, an enthusiastic promoter of new Polish music, conducted the Centuries-Old Songs. Aleksander Poliński, a fierce opponent of all things new and Karłowicz’s unyielding antagonist, called the composition “a precious musical pearl of rainbow splendour”! Today, the “modernist chaos” no longer causes irritation, nor would Karłowicz be reproved nowadays for his “eclecticism”. His symphonic music remains to us “a precious musical pearl of rainbow splendour”, a source of complex aesthetic satisfaction.

Dr Mieczysław Kominek

Read more:

Karol Szymanowski

The previous article:

Young Poland